The Endurance and the James Caird: Possibly the Greatest Boating Rescue Ever.

I hate the cold. When its 32F outside, I need two coats, a sweater, a shirt, and an undershirt … and I still shiver. But there’s something about temperatures well below that point that is captivating. Imagine the air crystallizing as you breathe, the ground sprouting flowers of ice, and a cold that isn’t wet. It’s almost pleasant.

That’s the kind of cold you’ll find at the poles. It’s so enchanting that one Englishman couldn’t get enough of it. Sir Ernest Shackleton was bit by the exploration bug in the early 1900s. It would eventually kill him, but it would also bring about one of the most captivating and heartwarming stories of an expedition that you’ll ever here. The story of The Endurance.

The Ship with the Perfect Name

Built to take tourists polar bear hunting in the Arctic, The Endurance was a Norwegian ship designed and crafted by a master shipbuilder who insisted that everyone who worked on his ships also have experience sailing on whaling or sealing ships. The result were sturdy boats that could take on Mother Nature’s worst – or at least, the worst that a wooden ship can withstand. When the tourism venture fell through, Shackleton bought the ship with the goal of taking it south, to Antarctica.

Shackleton looking overboard at Endurance being crushed by the ice. Photo via Wikipedia.

Shackleton’s family motto is “Fortitudine vincimus” which translates to “Through endurance we conquer”. He had no idea how accurate that motto would be when his ship set sail from Plymouth, England in August of 1914 with a carefully chosen crew. Or perhaps he did. An ad, most likely fake but fairly accurate, that Shackleton supposedly wrote read

“MEN WANTED: FOR HAZARDOUS JOURNEY. SMALL WAGES, BITTER COLD,

LONG MONTHS OF COMPLETE DARKNESS, CONSTANT DANGER, SAFE

RETURN DOUBTFUL. HONOUR AND RECOGNITION IN CASE OF SUCCESS.”

– SIR ERNEST SHACKLETON

I imagine he didn’t have loads of volunteers, although he did manage to recruit a biologist, geologist, and physicist, among others. Fund were tight and Britain was on the verge of war. World War I began at the same time that the ship set sail, and although Shackleton and his men offered to stay and offered the ship, stores and their services to help the nation, Churchill told them to go ahead and set sail. The war wasn’t expected to last more than 6 months.

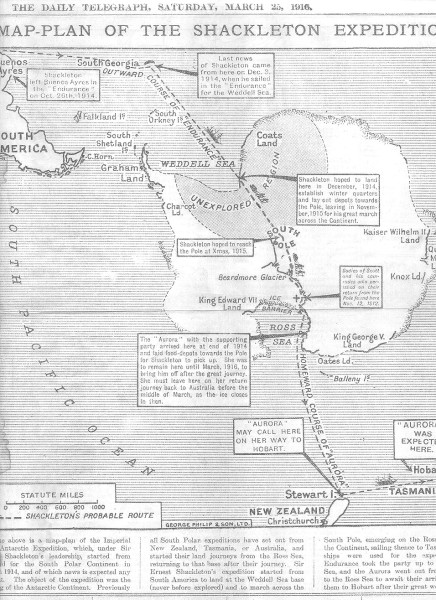

With a clear conscience and high hopes, Shackleton led his men to Argentina. They restocked quickly in Buenos Aires and then set sail for South Georgia Island. Norwegian whalers had a camp there, and Shackleton and his crew spent one month stocking their stores and preparing for their journey while getting to know the Norwegians whalers. That month of socialization would help them significantly later.

The day came to sail, and the ship left with a deck-load of coal, in addition to the normal coal stores below deck. It was December 5th, 1914, and everyone on board knew that the ship could easily be iced in on the Weddell Sea as it headed towards Antarctica. The pack ice grew thick, and crew members worked long hours, breaking up the ice and fighting to keep the boat from being frozen into it. Eventually, the ice won.

Ice-bound and Adrift

On January 18th, 1915, The Endurance could no longer sail. She was frozen into the pack ice. The crew played card and table games in a small heated room on the ship, lovingly nicknamed “The Ritz”. Outside, they played hockey and football. The ice began to push into peaks, and to grind against the wooden beams of the ship at night. On October 27th, 1915, The Endurance was abandoned. She sank on November 21st, 1915.

Nature’s slow and torturous devouring of The Endurance gave the men ample time to save supplies and stores for their journey, and at first two lifeboats. A party was sent back for the third, which proved a wise choice later in their ordeal. One of the boats, the James Caird, would later become a famous – albeit tiny – vessel.

Arctic spring began, and with it, the ice started to melt beneath them. By April 9th, 1916, the men made their way across a patch of open water by boat onto another large ice floe. On April 12th, they spotted Elephant Island in the distance. The sight of land was more than welcome. 497 days after their journey on the water began, they were relieved to set foot on land again.

The Greatest Small Boat Voyage in History

Still in good spirits and with excellent morale, the men also realized that Elephant Island was not salvation. It was a pit stop. No one came to the island, and no rescue ships would know to look for them there. Eight-hundred miles away, their most likely chance at survival lay on South George Island, where there trip started. Six men would make the journey for help. With 50-foot waves and vicious winds separating them from their destination, chances that one of the 20-foot-long lifeboats would stay afloat were slim, at best. Six men would have to make the journey for help.

The Cape Horn Rollers, infamous waves towering up to 60 feet high, blocked the path between the men and the safest inhabited landing in the region – South Georgia Island. In theory, there were closer places to sail to, but the seas were impassible in the Antarctic winter and the small boats. Even South Georgia Island was a gamble; the waves and vicious winds separating the men from their destination, made the chances that one of the 20-foot-long lifeboats would stay afloat slim at best.

Shackleton looked at his crew. Worsley was an excellent navigator. His help would be needed. Crean was hungry for adventure and an experienced hand on two prior expeditions – he wouldn’t stay behind even if ordered to, and he was a solid crewman. That made three. Shackleton needed three more volunteers. McNish offered. He was a smart choice; as the carpenter, having him on board could keep the boat afloat if things got rough – but he was also much older than most of the crew. Vincent was a rough character and might cause trouble if left behind on Elephant Island. He was also a solid hand on the sea. McCarthy was a strong sailor. They had a crew.

Of the three lifeboats, the James Caird was the strongest. A whaling boat, it had a double-end design and measured 22.5 feet in length. Still, it wouldn’t be able to make the journey without a little help. McNish used a mast laid horizontally to strengthen the boat’s interior, reinforced the overall structure, and sealed his work with lamp wick, seal blood, and oil paint. It wasn’t the best mix of materials, but it was what the crew had on hand.

Shackleton gave orders that Frank Wild would be in charge while he and his small crew left in the James Caird for help. The lifeboat was loaded down with 1,016 pounds of ballast in the form of boulders from Elephant Island and heavy sand bags stitched together from blankets. The carried enough rations for six men on a one-month journey, including powdered milk, Bovril (a salty beef extract popular in England), and biscuits. Two Primus stoves provided heat and a place to cook, while extra clothes and sleeping bags made from reindeer hide provided more warmth when needed.

The boat nearly capsized at launch on April 24th, but made it successfully out to sea, where a treacherous journey awaited. Ice surrounded them on all sides. Bizarre shapes of twisted, frozen water arose out of the sea, threatening the ship and the men on board it. Antarctic winter had arrived.

Worsley checked their position. Progress through the ice was slow and the sun was doing its best to hide from the small boat. They’d traveled only 45 miles on the first day.

By the second day of their voyage, the crew was 128 miles north of Elephant Island. The ice was far behind them, but their troubles had only just begun. They readjusted course to head slightly further north and to the east, towards South Georgia Island. To get there, they had to cross the Drake Passage, and intimidating swath or open sea that circles the globe unimpeded. Known for high winds, bad weather, and giant waves, even larger modern vessels find it intimidating.

The craft struggled to stay afloat in the torrid waters. Ballasts had to be moved constantly. On April 29th, the crew found themselves roughly 238 miles from Elephant Island. The ship was taking on water. The men struggled to bail the water out constantly. Temperatures dropped sharply, ice clung to the ship, and they had to use an axe to pitch the deck. Their clothes were covered in 7 months of sweat, dirt, and grime, and they were designed for the cold – but they weren’t waterproof. The sleeping bags, fashioned from Nordic reindeer hide, weren’t waterproof, either. The hairs kept washing off and clogging the ballast pump, making manually bailing the water an absolute necessity. The men were cold and adrift in some of the roughest waters on Earth in a boat smaller than the waves that surrounded them.

For 48 hours, the crew dropped a sea anchor. It was too dangerous to sail further. They lost the sea anchor. In an effort to lose some of the excess weight, the crew threw two of the reindeer hide sleeping bags overboard, along with much of their ballast. Weary, in pain, and facing frostbite, the men sailed on. Eventually, the sun came out. The air warmed, and the men took advantage of the break in cold, overcast, windy weather to dry their clothes and rid the boat of the ice crust that had formed on many parts of it. On May 4th, they were just 250 miles from South Georgia Island.

Trouble on the Sea

That evening, nature came back with a vengeance. Around midnight, a powerful storm with massive waves and strong winds battered the small craft. After hours of an exhausting fight against the waves, Shackleton shouted to his crew to look to the sky. He had seen a large swath of white, which looked to be a thin spot in the cloud.

It wasn’t.

“A moment later I realized that what I had seen was not a rift in the clouds but the white crest of an enormous wave. During twenty-six years’ experience of the ocean in all its moods I had not encountered a wave so gigantic.

It was a mighty upheaval of the ocean, a thing quite apart from the big white-capped seas that had been our tireless enemies for many days. I shouted ‘For God’s sake, hold on! It’s got us.’ Then came a moment of suspense that seemed drawn out into hours. White surged the foam of the breaking sea around us. We felt our boat lifted and flung forward like a cork in breaking surf.”

-Sir Ernest Shackleton

The cooking stove was soaked, and most of the rations were destroyed. By 3AM, the stove was functioning again, but the waterlogged men were ready for rest. They were thirsty and tired, but they pressed on. Hope caught ahold of them – on May 7th, Worsley’s calculations showed that they were less than 100 miles from South Georgia Island.

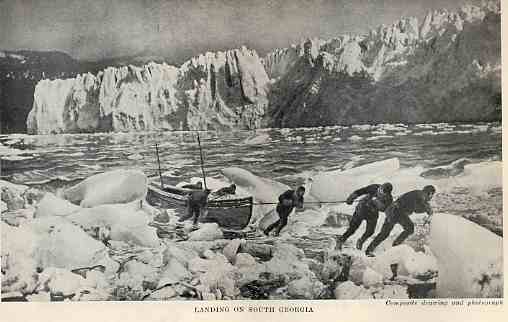

The wave and the storm that accompanied it hadn’t hindered their progress. On May 8th, the men saw sea birds, seaweed, and eventually, land. Late in the evening on May 10th, after trying unsuccessfully on the 9th, the James Caird was finally able to land. Exhausted to the point of collapse, they pulled their ship on shore and set up a small camp, which they nicknamed ‘Peggotty Camp’ in honor of the family in Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. Today, the site of their camp is known as Peggotty Bluff.

Land at Last

That first night, Shackleton relived the worst moments of their journey. He woke the entire camp in terror as he stared at the snowcapped cliff above him, in the grips of a nightmare that convinced him it was another massive wave.

There was just one problem… they were on the wrong side of the island, and what separated them from a rescue ship that could save their companions was a range of mountains so difficult to cross that no one bothered to claim them. Sharp peaks, ice, snow, gravel, and quickly-changing weather stood in their way.

Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean set out for the whaling camp on May 15th, 1916. Vincent and McNeish were too exhausted from the ordeal at sea to cross the treacherous mountains, and McCarthy was left to care for them. The trio made their way quickly up to 4,500 feet above sea level, and although they were tired, they knew rest wasn’t an option. The cold would quickly kill them if they stayed at that height. They dropped 900 feet by sliding down a slope like kids, and then climbed another peak to 4,000 feet above sea level.

Along the way, they sat to eat. The second peak was a tempting spot to rest for the night, but the temperature was dropping and they noticed one major problem. They were on a glacier. There were no glaciers on the way to the Norwegian whalers’ settlement. They’d gone off course and had to double back.

Eventually, the ragged and scruffy group made their way over the mountains, with only 5 minutes sleep in 36 hours. As they descended the mountain, the temperature rose slightly. Faced with a minimum 5 miles walk or what looked like a quick but treacherous descent, they chose the fast route. It was easier than they’d first guessed – they walked through a mountain stream towards the whaling camp without incident until they found themselves standing in a shallow mountain lake with a 30-foot waterfall between them and their destination.

Crean was the heaviest, so they lowered him first. When he emerged safe on the other side, the rest followed suit. In the distance, they could clearly see the Norwegian camp.

A Safe Arrival

After a year at sea and a difficult climb on land, the men looked nothing like themselves. They arrived at the manager’s house, but he failed to recognize them. He did, however, welcome them in when they told him who they were. Shackleton and his crew recounted their adventures, and on May 19th, a motorboat picked up the rest of the Peggotty Camp crew.

A depiction of the James Caird landing at South Georgia at the end of its voyage on 10 May 1916. Courtesy Wikipedia.

Shackleton, with the help of the Chilean government and private donors, launched numerous attempts to rescue the 22 stranded men on Elephant Island. On August 30th, 1916, a boat finally reached the men. Shackleton was on board. All 28 of The Endurance’s crew survived unharmed, minus a little frostbite. Their adventure is one of the most impressive and intimidating of the Antarctic, and has been made into several movies, TV specials, and books. It’s enough to scare the faint of heart and to inspire would-be explorers.

I’m content to hear the tales of high seas adventure and treacherous mountain crossings from the comfort of my living room – although I do enjoy the occasional trip and wouldn’t mind seeing the Antarctic one day. What about you? Are you up for adventure or would you prefer to live vicariously through someone else’s tales?