Chrome Dome: Nothing says we’re pals like a nuclear bomb

Operation Chrome Dome isn’t talked about much in the US. No matter how we feel about government, most of us are pretty sure no one will drop a nuke on us out of the blue. I mean, if you were sitting on top of the most dangerous weapons known to man, you might take extra safety precautions to protect innocent people.

Right?

Somehow, despite plenty of red tape and careful treatment, more than 30 nuclear accidents have happened since we created the H bomb. Taking home the prize for worst nuclear weapon mistakes in history, under Chrome Dome the United States managed to accidentally bomb not one, but (at least) two of its allies in the 1960s. Denmark and Spain both said they harbored no hard feelings towards us after those little slip ups, thankfully.

Ready to find out how those accidental bombings happened? Let’s dig into the history of the Palomares and Thule accidents.

Operation Chrome Dome

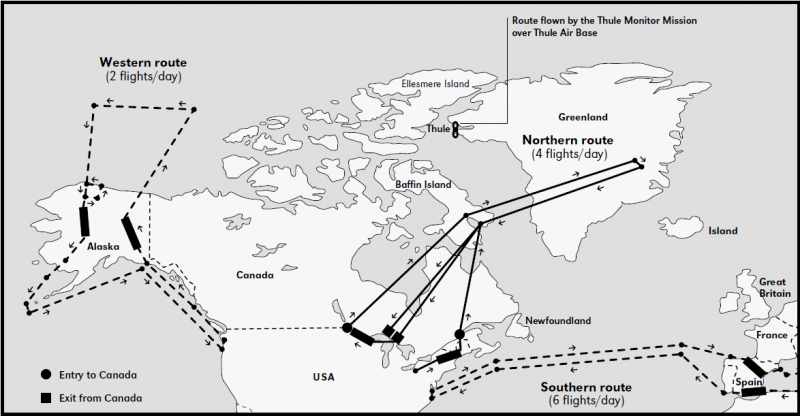

Chrome Dome routes from 1966

A top secret operation that lasted from 1960-1968, Chrome Dome involved providing the United States and its allies with the constant ability to drop a nuclear bombs on the USSR in case of an attack. B-52 bombers circled American and ally airspace to points along the USSR border and back, routinely lasting 24 hours or more. As a result, in-air refueling was a part of these missions, too.

During Operation Chrome Dome, we had at least 5 “oops” moments with nukes, but the two worst disasters were the 1966 Palomares incident and the 1968 Thule affair. Thule led to the close of this program, along with the availability of long-range nuclear missiles. Flights became obsolete. As anyone in Greenland or Spain can tell you, that’s a good thing.

The 1966 Palomares Incident

A field of B-52 bombers in storage.

Imagine a peaceful coastal village in Spain at mid-day. There were 1,600 residents here, and nearly half were British expats. It was 10:30 in the morning on January 17th, 1966. The holidays recently ended and children sat restlessly at their desks in school, farmers were busy tending tomato fields, and fisherman were hauling in the morning’s catch.

31,000 feet above Palomares, a B-52 Stratofortress bomber rushed towards a KC-135 Stratotanker for in-air refueling. On its third refuel in a 24-hour round trip from the U.S. to Italy as part of Operation Chrome Dome’s Southern airborne alert route, the bomber was flown by Relief Captain Larry G. Messinger while the Captain, 29-year-old Charles J. Wendorf, rested.

Wendorf’s wife, Betty, had a bad feeling before the flight. She asked him not to go, but orders are orders. Wendorf said goodbye to his wife and three kids on January 16th before boarding the bomber for one of his regular Chrome Dome flights. He’d been making similar trips for five years; the long flight was routine.

Messinger approached the KC-135 at 500 miles per hour. The operator on the KC-135 told him to watch his enclosure, but in-air refueling was routine for both crews at this point. And then it happened. The bomber overshot the KC-135’s fuel boom, and WHAM!, the left wing of the bomber was ripped off in mid-air by the trailing boom.

In an instant, the KC-135 was destroyed and everyone aboard was killed. Onboard the B-52, chaos broke out. The plane erupted in flames and its crew ejected as the bomber broke into pieces over Spain and the Mediterranean.

As the B-52 fell into a steep nose dive and broke apart, its cargo fell over the village of Palomares and the nearby Mediterranean.

Its cargo was deadly – 4 hydrogen bombs, each 100x more powerful than the bomb the United States dropped on Hiroshima. If they exploded, much of Spain could be destroyed and the radioactive fallout could wreak havoc on the health and habitability of Europe for decades to come.

Luckily, the only way for the hydrogen bombs to fully detonate required the crew to arm them beforehand. Unarmed, they still packed power and carried a dirty bomb that would detonate on impact, spreading plutonium and shrapnel over a significant area.

Two of them did.

A third fell without exploding into a nearby dry riverbed and was partially buried, while the fourth bomb released its parachute and drifted out over the Gulf of Vera in the Mediterranean Sea, finally resting more than 2,500 feet under water.

Within hours, U.S. personnel were on the scene. Soon, more than 2,000 members of the U.S. military and Spanish Civil Guard were in Palomares, cleaning up soil and vegetation that was contaminated by the bombs and recovering the wreckage. It took several months to locate the bomb that fell in the sea. Eventually, a local fisherman’s account outwitted an IBM computer’s attempts to find the underwater nuke. On April 7th, 1966 the last bomb was recovered.

More than 50 years after the Palomares incident, some residents still recall the day fire rained from the sky. More than 500 of the village’s inhabitants have filed health claims with the U.S. government and been reimbursed. Soil in the area remains contaminated, and Spain and the United States are still working on cleanup initiatives.

The last recovered nuke from Palomares.

The 1968 Thule Affair

The Palomares accident brought attention to the danger of nuclear bombs being flown around over allied territory, but it didn’t end Operation Chrome Dome. Two years later, the Thule accident would have that honor.

In the northern Greenland, owned by nuclear-neutral Denmark, the U.S. had an air base. Above it, B-52 bombers loaded with hydrogen bombs ran continuous patrols, waiting for the day when the USSR might turn the Cold War into a hot one. The base wasn’t exactly located in a warm place, and the bombers didn’t have great heating or very comfortable seats. As a result, the crews improvised ways to make the flights bearable.

Cockpit of Boeing B-52D-30-BW (S/N 56-0665), at the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

That improvisation would lead to a deadly accident on January 21, 1968.

The flight crew that day included Captain John Haug, Captain Curtis Criss, Major Alfred D’Mario, Co-pilot Leonard Svitenko, Staff Sargeant Calvin Snapp (gunner), and three others. D’Mario, aware of the uncomfortable seats and rest areas, brought three cloth-covered cushions with him for the flight, and set them on top of a heating unit in the lower deck.

They took off from Plattsburgh Air Force Base in New York and flew to Thule, where they began a figure-eight holding pattern above Baffin Bay and the Thule base. It was an uneventful flight, refueling went smoothly, and the captain sent his co-pilot, Svitenko, to take a rest. D’Mario took his place.

Temperatures in the cabin were uncomfortably chilly, so D’Mario opened an engine bleed valve to draw more heat. Due to a malfunction in the heater, it got a little too hot. The crew began to smell burning rubber. There was a fire onboard, and they knew they didn’t have much time to find it.

Looking for the source of the smell, the crew’s navigator searched intensely for the flame. He entered the lower deck twice, but saw nothing. Meanwhile, behind a metal box where he hadn’t thought to look, D’Mario’s cushions were burning. By the time he discovered the source of the fire, it was too late. Two fire extinguishers onboard the bomber failed to put out the blaze.

Captain Haug knew the plane was in trouble. He radioed the Thule base, requesting emergency permission to land at 3:22 in the afternoon, but the plane would never make it to the base. All of the fire extinguishers were depleted, the cockpit was filled with smoke, and the electrical system no longer responded. When D’Mario confirmed that the plane was over Thule Air Base, four of the crewmen ejected, followed shortly after by D’Mario and Haug.

Svitenko was left without an ejection seat and attempted to exit one of the lower hatches. He hit his head and died as a result.

An aerial view of Thule Air Base.

One by one, the surviving crew were rescued by native Greenlander sled dog teams. One of the last to be rescued was Captain Criss, who survived on an ice floe for 21 hours. He suffered hypothermia, and only survived thanks to his choice to use his parachute as a blanket.

A mere 7.5 miles north of Thule, the unmanned plane made a 180° turn and then fell out of the sky, a fiery ball of jet fuel and metal. The plane’s cargo of four hydrogen bombs detonated their highly explosive components on impact. Unarmed, the nuclear components did not detonate. The explosion did spread significant radiation across a wide area, however, and much of the plane’s wreckage sunk to the bottom of the ocean after hours of burning through more than 102 tons of jet fuel on the ice.

On the ice, only a few small bits of wreckage and a large black stain remained after the crash. Emergency cleanup operations began almost instantly under the code name Project Crested Ice, nicknamed Dr. Freezelove by those involved. The sea ice would melt in spring, and the risk of contaminants seeping into the water was high.

Within 9 months, more than 700 Danes and Americans had cooperated to remove the contaminated ice, water, and materials from the site, representing over 70 government agencies from the U.S. alone. Cleanup cost $9.4 million USD.

The remains of three of the nukes were initially accounted for, and the fourth was not recovered. It’s not clear if the Danes knew that the fourth wasn’t found, and the resulting scandal has shown up in Danish papers more than once. Additionally, the presence of nuclear weapons in Denmark contradicted the country’s official position regarding nuclear arms and resulted in a scandal dubbed “Thulegate”.

Rescue of Ssgt Calvin Snapp.

Cleanup workers at a tank farm that held materials from the cleanup project in Denmark experienced extremely high rates of cancer and many died of the condition. Many Thule-area residents, tank farm workers, and other cleanup workers involved in the accident have repeatedly fought for compensation from the Danish government, and some received awards of 50,000 kroner, but the fight for full recognition of the crash’s impact still continues and so far has resulted in the release of numerous classified documents about the United States’ nuclear program and activities in Denmark, as well as the Danish government’s position.

What about Accidents in the U.S.?

The United States has a policy of staying quiet about domestic nuclear accidents. When they happen overseas publicity is inevitable, but at home, not so much.

Nuclear bomb that fell in Goldsboro, North Carolina.

According to history.com, “As a means of maintaining first-strike capability during the Cold War, U.S. bombers laden with nuclear weapons circled the earth ceaselessly for decades. In a military operation of this magnitude, it was inevitable that accidents would occur. The Pentagon admits to more than three-dozen accidents in which bombers either crashed or caught fire on the runway, resulting in nuclear contamination from a damaged or destroyed bomb and/or the loss of a nuclear weapon.”

Off the coast of Georgia in the Wassaw Sound, in the Puget Sound off Washington State, and in the swamps outside Goldsboro, North Carolina, the military has yet to recover two nuclear bombs and a uranium core.

I know where I won’t be fishing…