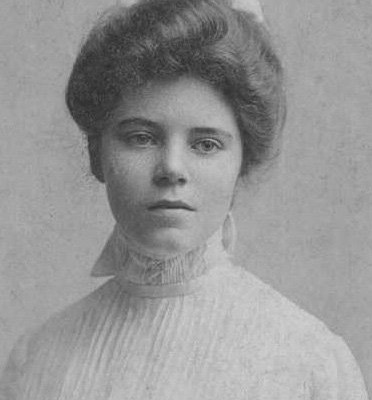

Alice? Alice. Who the heck was Alice Paul?

On January 11, 1885 on a large Quaker farm in New Jersey, the Paul family welcomed their first child, Alice. Although many farm girls of her era boasted a muscular build, Alice was always slightly framed. She didn’t convey an image of physical strength, but her character was one of the toughest the women’s suffrage movement would encounter.

Alice’s mother was a part of the suffragist movement, as were many Quaker women of the time. Quakers believed in equality, and worked hard to achieve it. This was true in education as well as in voting rights.

Alice Paul’s Education

In 1864, Alice Paul’s grandfather, Judge William Parry, had helped found Swarthmore College. Her mother Tacie attended the institution, but as married students weren’t allowed at the time, she dropped out after marrying at the end of her third year. She also made a promise to herself that all of her children would get the same opportunity.

Alice Paul entered the school in 1901, and while there she flourished as a scholar. Her undergraduate degree was in biology, but Alice was interested in many subjects, served on student government, and was named an Ivy Poetess. She was an excellent scholar and after completing her degree, decided to continue her education in practice in England, as a part of the settlement movement. For her, all of life was a learning experience.

Alice Paul had spent two years working in the settlement movement in New York, but jumped at the chance to move to England and to study social work in Birmingham at the Woodbridge Settlement. That move would radically change her approach to social issues, her idea of the effectiveness of social work, and the course her life would take. Alice Paul would soon become a militant suffragist.

The English Suffragist Movement and Alice Paul

Although stories vary as to how they met, Alice Paul made quick friends with the mother-daughter suffragists, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. In her three years in England, Alice was transformed from a quiet Quaker farm girl to a strong-willed advocate for women’s right to vote with a tenacious spirit – in part strengthened by multiple trips to jails in England. Her hunger strikes in British jails led to cruel forced feedings which were more damaging to her body than the actual hunger strikes, and the companionship of women committed to a cause that crossed international boundaries.

In England, Alice was very active in suffragist movements – and not just from behind bars. She joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, often touted as the original “suffragettes”, the organization run by her friend Emmeline Pankhurst. It was there that she embraced her ability to confront injustice head on despite a fear of public speaking. The British suffragettes were fighting a strong war. They used every nonviolent means possible to make their point, including picket lines, parades, and public speeches. Their motto was one Alice Paul quickly took a liking to – “Deeds not words.”

Alice Paul recognized one fatal flaw in the American women’s suffragist movement. It was dying as a result of tactics that were too passive. Fighting a real woman’s fight would take more mettle than the movement had shown. She returned to the US ready to put the lessons she’d learned into action.

Return to the United States

When Alice Paul came back to the United States in 1910, she returned to academia, where she completed her PhD in Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. By 1912, she’d launched fully into a career as a suffragist and joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), where she quickly encountered the flaw she’d noted while in England; passive and conservative tactics that wouldn’t lead to quick results.

Alice Paul was set to revolutionize politics for American women.

While at NAWSA, Alice led the Congressional Union part of the organization. On March 3, 1913, the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, Alice led a massive parade of more than 5,000 women suffragists to the White House. The parade started as a calm and peaceful protest, complete with horses. Shortly after it commenced, however, the women who marched were attacked by bystanders. Still, their strong numbers and powerful motivation led them forward. According to a PBS article, “The festivities drew hundreds of thousands of spectators, but as the day progressed, some onlookers began assaulting the marchers. The police did little to stop the attack. Despite the violence, the parade succeeded in obtaining Paul’s objective: focusing national attention on the women’s suffrage issue.”

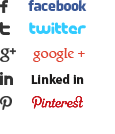

The parade’s date was no accident – Alice Paul recognized that President Wilson was key to the suffragist movement. She wanted to focus her efforts on him directly. Her approach wasn’t universally appealing. When Alive took over, the Congressional Union’s main goal was to gain the passage of a federal amendment for woman suffrage. She decided to split the organization from NAWSA in 1914 and surrounded herself with likeminded suffragists who were ready for more immediate change. They were willing to face extreme conditions, abuse, and slander in order to pass women’s suffrage.

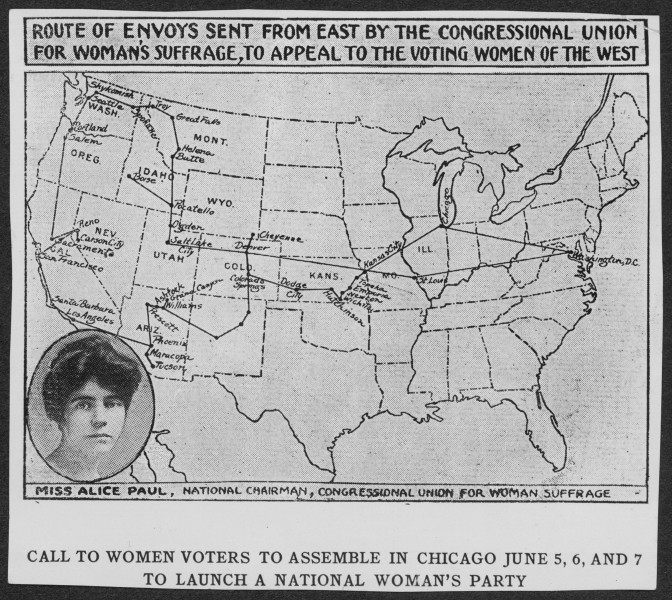

By 1916, Alice Paul had even bigger dreams. She formed the National Women’s Party to make her vision a reality, and brought many of her more militant suffragist friends with her. On January 10, 1917, Alice Paul led a group of protesters to the White House, where they formed a picket line. These ‘Silent Sentinels’ are believed to be some of the first, if not the first, protestors to picket at the White House. Their signs directly targeted the president with comments like “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?”

At first, Alice Paul’s picketers were treated as a curiosity. A passing fad, perhaps. Bystanders got used to them, waved greetings, nodded, and went about their business. When the United States entered World War I, however, Alice’s tactics gained new and harsh criticisms from a public that viewed them as distracting from the ‘real’ issue – the war. She managed to greatly irritate the President and some sectors of the public, which landed her and her fellow picketers in prison on charges like “obstructing traffic” for which they were fined and refused to pay. Oddly enough, this might have helped her cause.

Alice was sentenced to seven months in jail, and along with her fellow suffragists, was subjected to harsh conditions. According to the Alice Paul Institute,

“The arrested suffragists were sent to Occoquan Workhouse, a prison in Virginia. Paul and her compatriots followed the English suffragette model and demanded to be treated as political prisoners and staged hunger strikes. Their demands were met with brutality as suffragists, including frail, older women, were beaten, pushed and thrown into cold, unsanitary, and rat-infested cells. Arrests continued and conditions at the prison deteriorated. For staging hunger strikes, Paul and several other suffragists were forcibly fed in a tortuous method. Prison officials removed Paul to a sanitarium in hopes of getting her declared insane. When news of the prison conditions and hunger strikes became known, the press, some politicians, and the public began demanding the women’s release.”

It was a rough fight, but they didn’t falter.

By November of 1918, all of the women were freed. Shortly after, President Woodrow Wilson voiced his support for a women’s suffrage amendment. Alice Paul’s tactics, combined with the softer efforts of NAWSA, Carrie Chapman Catt and other suffragists, persuaded President Woodrow Wilson to make the amendment a wartime priority. They also changed the future of picketing forever – charges against Alice Paul and her nonviolent civil disobedience were on trial in a U. S. Court of Appeals. The case was thrown out, and opened the door to future generations of protestors – now a common sight in front of the White House.

The 19th amendment to the United State Constitution owes its existence to Alice Paul and women like her. Any woman who casts a ballot owes her vote to Alice, too. The text of the amendment is inclusive and simply states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

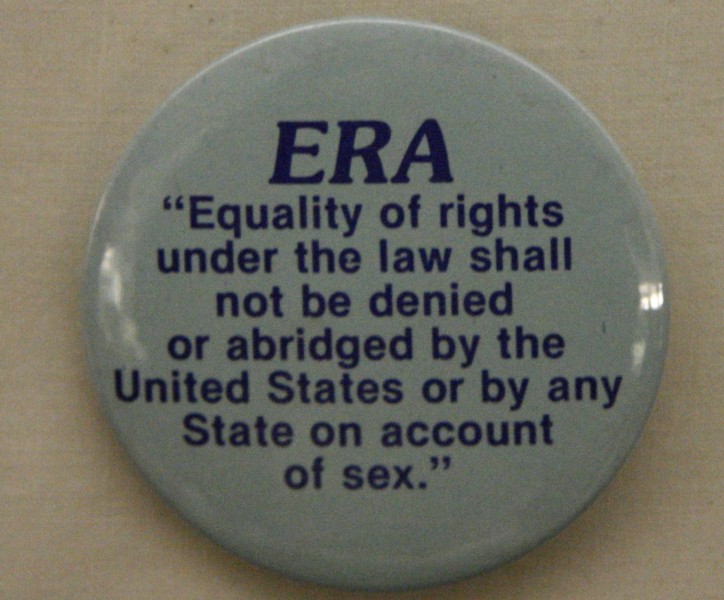

Victory was sweet, but Alice Paul wasn’t done fighting. At 37 years of age, she obtained a degree in law with one specific goal. Alice drafted the first version of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1922 – a measure which has still NOT been passed. She fought for the inclusion of an Equal Rights Amendment to prevent discrimination based on gender in the US until forced to retire in 1972 based on her failing health, and also fought to see gender equality measures included in the UN Charter.

In 1974, Alice Paul suffered a massive stroke. She died three years later, on July 9, 1977 in New Jersey. Today her childhood home, Paulsdale, is a National Historic Landmark and the home of the Alice Paul Institute – an organization that works to continue Alice’s mission. Her face has been featured on postage stamps and coins, and she is portrayed in the move Iron Jawed Angels as well as inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. And we can’t forget the Bad Romance parody, Women’s Suffrage:

<iframe width=”420″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/rLQyhBp_qtc” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen></iframe>

But the Equal Rights Amendment Alice dedicated the last part of her life to has become a topic for debate and divides feminists and politicians. Unlike her suffrage success, it still hasn’t been ratified nationally, although many states have chosen to ratify it.

Button showing the ERA amendment. Photo by David on Flickr.