The Election of 1825: John Quincy Adams’ crazy path to the White House

Let’s talk politics for a minute. Imagine a time when Democrats and Republicans were a part of the same party. Seems impossible, doesn’t it?

Get ready for a bizarre trip into early American history…it’s 1824 and the Democratic-Republican Party has won the last six presidential elections. High on that winning streak, they’re poised to take the White House again, but things are about to get weird.

(Oh, but just to be clear, the National Republican Party that later evolved from the Democratic-Republican Party has nothing to do with today’s GOP. In fact, the GOP evolved from a strong anti-slavery movement in opposition of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and had almost no presence in the South…but I’ll get to that some other time.)

Back to the election of 1824.

In 1824, the contenders for the White House who stuck through the tough election season and prepared for the Presidential ballot were some fairly famous guys. You’ll recognize them right away:

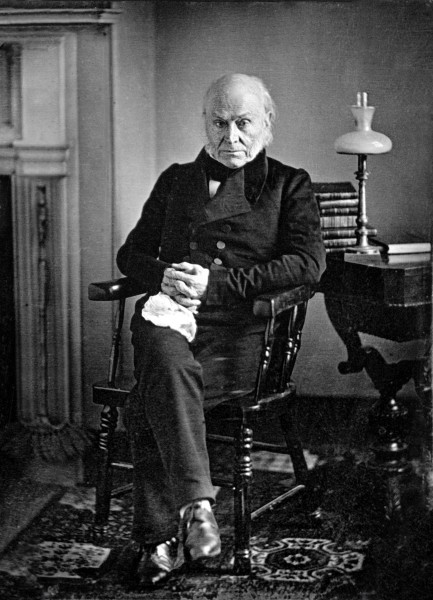

- Secretary of State John Quincy Adams

- House Speaker Henry Clay

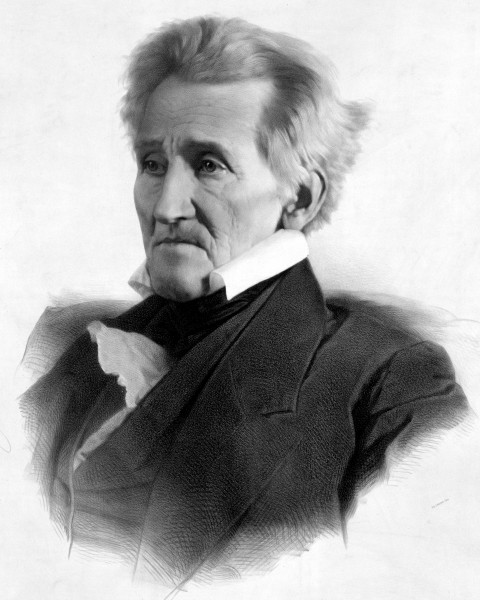

- Senator Andrew Jackson

- Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford

John Quincy Adams was so eager to be at the top of the United States’ chain of command, he ran for Vice President, too.

There’s one thing all of those candidates had in common, apart from being big names in U.S. history – they were ALL members of the Democratic-Republican Party. John Quincy Adams came from a long line of Federalists, but by the time election season rolled around, he knew that wasn’t going to work out. In fact, the Federalist party was in such a bad position that in 1820, President James Monroe of the Democratic-Republican Party ran unopposed for his second term. The term limit didn’t exist at that point, but like most good presidents, Monroe declined to run for a third term.

…and that’s how we wound up with four presidential candidates from the same party.

Candidate Nominations in the Presidential Election of 1824

Caucusing is an informal process, and when your party is guaranteed the win it can be hard to find the motivation to attend another boring meeting. It’s not surprise that almost no one showed up at the Congressional caucus in 1824, but not many people were happy with what happened there, either. Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford was nominated as the presidential candidate with Albert Gallatin as his running mate.

Gallatin wasn’t a popular guy. He also had a poor stomach for mudslinging in politics – especially when he was on the receiving end of it. He dropped out. Crawford wasn’t in the best shape, either. He’d had a stroke in 1823. Not the best pre-election health for a presidential candidate.

Andrew Jackson was the popular favorite – at least, with the general public. A career politician, he managed to upset his fellow congressmen, which left him only 1 vote in the caucus. Clay was a weak candidate, although he managed to gain the attention of voters in Missouri, Ohio, and Kentucky. And then there was Adams…

John Quincy Adams had the political machine working in his favor. He was wildly popular among Federalists, and even attracted the attention of quite a few Democratic-Republicans. The electorate loved him. Jackson was terrified of him – Adams was his only real competition in the race for the White House. As for Vice Presidents, John C. Calhoun was a shoe in. Jackson and Adams both took him as running mate. The man couldn’t lose.

Was The Article Title a Typo?

I can hear you thinking to yourself, “the title said 1825. Why is she saying 1824 over and over again? Did she make a mistake or something?”

Nope. No mistake.

Here’s the thing…if this election had gone as planned, I would have written 1824 in the title. It didn’t. The 1824 election was one of very few in American history where the House of Representatives had to cast the final vote.

Back in the day, voters did the campaigning for candidates. It was almost all volunteer based, and there weren’t any PACs or super PACs to deal with. People made up songs about candidates, wrote essays, gave speeches, you name it. Getting directly involved in your campaign didn’t even help a candidate that much. Before he became the VP of choice, Calhoun tried to run for President. Despite frequent participation and newspaper contributions, he really didn’t get too much of the public’s attention – kinda’ like the kid who is always raising his hand in class, so often that the teacher just starts to ignore him.

Sound like heaven for a candidate? It was for Jackson. Despite stiff competition from Adams, he took home the bulk of the electoral vote. There was just one teeny, weeny problem.

He only won 41.4% of the electoral vote, with 99 votes. Adams pulled 30.9%; 84 votes. None of the candidates managed to take home the 131 electoral votes needed to declare a majority. Things were about to take a historic and some would say morally-questionable turn.

The final vote was left to the House of Representatives (incidentally, this was also the FIRST election where the popular vote was counted). Tensions were high. Congress divided. The race was down to 3 candidates, as good ol’ Henry Clay, who had 37 electoral votes and very little love for Jackson, was disqualified.

Clay and Adams had a lot in common. They were members of an informal club of sorts – the National Republicans. He is thought to have convinced his supporters to cast their ballots for John Quincy Adams … in exchange for a cushy job in the administration as Secretary of State. Just like Hillary Clinton is campaigning hard for president after a term as Secretary of State, the position was a springboard to the presidency in the early 1800s.

Clay agreed.

Say hello to the moment known as the first Corrupt Bargain in American election history. Of course Jackson’s supporters, known as Jacksonians, weren’t too happy with the development. They worked hard to make Adams’ life as president miserable and managed to pave the way for President Andrew Jackson to take office the following election. I guess Adams learned a bit about Karma in 1828 …

John Q. Adams first term was a considered a colossal flop at the time. Basically, a hostile congress and increasing tension inside his party between the soon-to-be Democrats and the National Republicans. When he ran for re-election, Andrew Jackson beat him by a landslide.