What to Know About The Space Shuttle Columbia Disaster

The STS-107 crew includes, from the left, Mission Specialist David Brown, Commander Rick Husband, Mission Specialists Laurel Clark, Kalpana Chawla and Michael Anderson, Pilot William McCool and Payload Specialist Ilan Ramon. (NASA photo)

Columbia was the first space worthy shuttle in NASA’s fleet and first to launch in 1981.

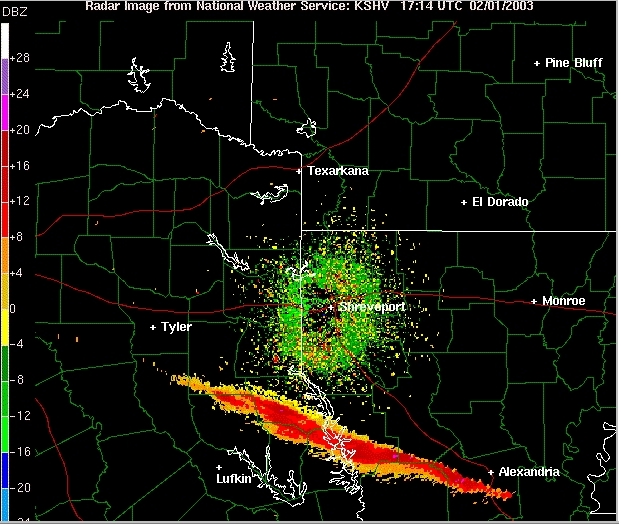

The Space Shuttle Columbia disaster occurred on February 1, 2003, when the shuttle disintegrated over Texas and Louisiana as it reentered Earth’s atmosphere, killing all seven crew members. Here’s how it happened.

The Cause

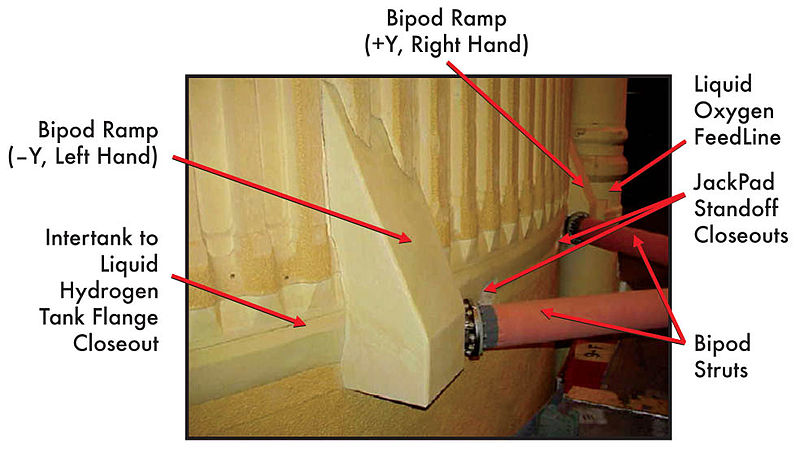

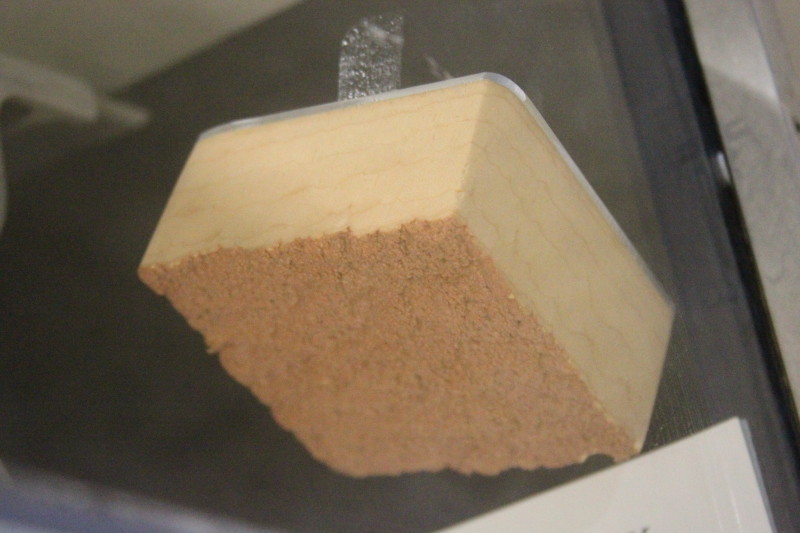

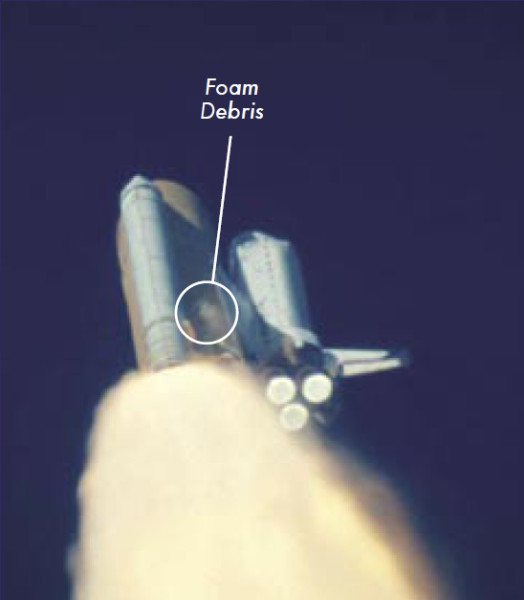

About 82 seconds after launch from Kennedy Space Center, a suitcase-size piece of foam broke off from the External Tank, striking Columbia’s left wing reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC) panels, allowing hot gases to enter the wing when Columbia later reentered the atmosphere. At the time of the foam strike, the orbiter was traveling at Mach 2.46 (1,870 mph).

Most previous shuttle launches had seen similar, albeit minor damage to all of the shuttles, due to foam shedding from their External Tanks. However, the risks were deemed acceptable. After the launch, some engineers suspected the damage, but NASA managers limited the investigation, under the rationale that the Columbia crew could not have fixed the problem.

Foam shedding had been observed on four previous flights: STS-7 (1983), STS-32 (1990), STS-50 (1992) and most recently STS-112 (just two launches before STS-107). All affected shuttle missions completed successfully.

After STS-112, NASA leaders analyzed the situation and decided to go ahead under the justification that…

“The ET is safe to fly with no new concerns (and no added risk) of further foam strikes.”

High resolution film taken during lift-off of STS-107 was reviewed overnight and confirmed foam debris striking the left wing, potentially damaging the thermal protection on the Space Shuttle.

In 2013, retired NASA official Wayne Hale recalled what Director of Mission Operations John Harpold told him before Columbia’s destruction…

“You know, there is nothing we can do about damage to the Thermal Protection System. If it has been damaged it’s probably better not to know. I think the crew would rather not know. Don’t you think it would be better for them to have a happy successful flight and die unexpectedly during entry than to stay on orbit, knowing that there was nothing to be done, until the air ran out?” -Wayne Hale, NASA Official

Before the flight NASA believed that the RCC (reinforced Carbon Carbon leading edge panels) was very durable. Charles F. Bolden, who worked on tile-damage scenarios and repair methods early in his astronaut career, said in 2004…

“Never did we talk about [the RCC] because we all thought that it was impenetrable … I spent fourteen years in the space program flying, thinking that I had this huge mass that was about five or six inches thick on the leading edge of the wing. And, to find after Columbia that it was fractions of an inch thick, and that it wasn’t as strong as the Fiberglas on your Corvette, that was an eye-opener, and I think for all of us … the best minds that I know of, in and outside of NASA, never envisioned that as a failure mode.” – Charles F. Bolden, NASA official.

On January 23, flight director Steve Stich sent an email to Columbia, informing commander Rick Husband and pilot McCool of the foam strike – while unequivocally dismissing any concerns about entry safety.

“Experts have reviewed the high speed photography and there is no concern for RCC or tile damage. We have seen this same phenomenon on several other flights and there is absolutely no concern for entry.” – Steve Stich, Flight Director

Timeline of the Disaster

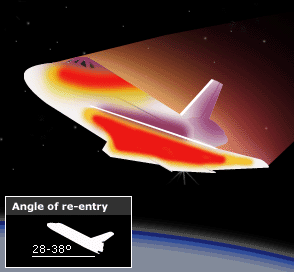

Feb 1, 2003 8:44 am – As Columbia descended, the heat of reentry caused wing leading-edge temperatures to rise steadily, reaching an estimated 2,500 °F during the next six minutes.

8:48 am – A sensor on the left wing leading edge spar showed strains higher than those seen on previous Columbia re-entries.

This was recorded only on the Modular Auxiliary Data System, which is like a flight data recorder, and was not sent to ground controllers or shown to the crew.

8:50 am – Columbia entered a 10-minute period of peak heating, during which the thermal stresses were at their maximum. Speed: Mach 24.1; altitude: 243,000 feet.

8:53 am – Various people on the ground saw signs of debris being shed. The superheated air surrounding the Orbiter suddenly brightened, causing a streak in the Orbiter’s luminescent trail that was quite noticeable in the pre-dawn skies over the West Coast. Observers witnessed four similar events during the following 23 seconds.

8:59 am – A broken response from the mission commander was recorded: “Roger, uh, bu – [cut off in mid-word] …” It was the last communication from the crew and the last telemetry signal received in Mission Control.

8:59 am – Hydraulic pressure, which is required to move the flight control surfaces, was lost at about 8:59:37. At that time, the Master Alarm would have sounded for the loss of hydraulics, and the shuttle began to lose control, beginning to roll and yaw uncontrollably, and the crew would have become aware of the serious problem.

9:00 am – Videos and eyewitness reports by observers on the ground in and near Dallas indicated that the Orbiter had disintegrated overhead, continued to break up into more and smaller pieces, and left multiple contrails, as it continued eastward. In Mission Control, while the loss of signal was a cause for concern, there was no sign of any serious problem. Before the orbiter broke up at 9:00:18, the Columbia cabin pressure was nominal and the crew was capable of conscious actions. The crew module remained mostly intact through the breakup, though it had lost enough structural integrity that it lost pressure, and was completely depressurized no later than 9:00:53.

9:01am – The crew module, intact to this point, was seen breaking into small subcomponents. It disappeared from view at 9:01:10. The crew, if not already dead, were killed no later than this point.

9:05am – Residents of north central Texas, particularly near Tyler, reported a loud boom, a small concussion wave, smoke trails and debris in the clear skies above the counties east of Dallas.

9:12 am – After hearing of reports of the shuttle being seen to break apart, Entry Flight Director LeRoy Cain declared a contingency (events leading to loss of the vehicle) and alerted search-and-rescue teams in the debris area. He called on the Ground Controller to “lock the doors”. Two minutes later, Mission Control put contingency procedures into effect. Nobody was permitted to enter or leave the room, and flight controllers had to preserve all the mission data for later investigation.

Later that day, President George W. Bush addressed the United States…

“This day has brought terrible news and great sadness to our country … The Columbia is lost; there are no survivors… The cause in which they died will continue… Our journey into space will go on.”

The Recovery

More than 2,000 debris fields were found in sparsely populated areas. Along with pieces of the shuttle and bits of equipment, searchers also found human body parts, including arms, feet, a torso, a skull, and a heart. All recovered non-human Columbia debris is stored in unused office space at the Vehicle Assembly Building, except for parts of the crew compartment, which are kept separate.

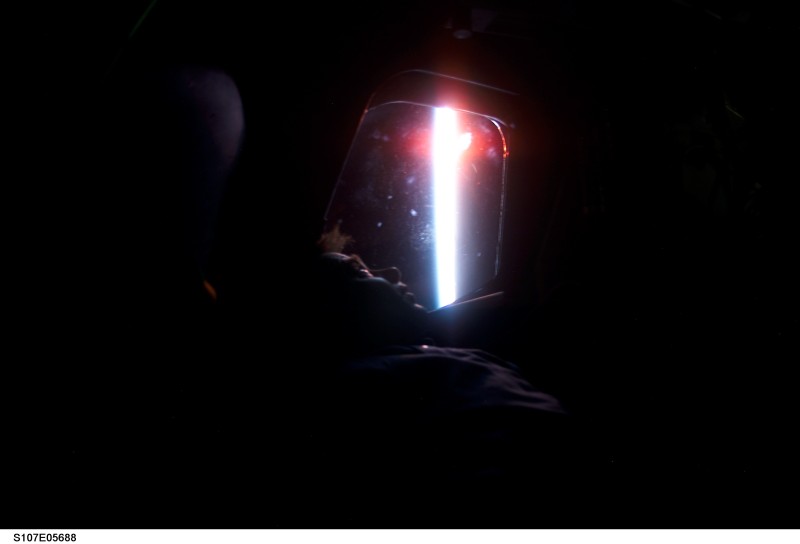

The recovered items include a videotape recording made by the astronauts during the start of re-entry. The 13-minute recording shows the flight crew astronauts conducting routine re-entry procedures and joking with each other. None gives any indication of a problem. The video shows the flight-deck crew putting on their gloves and passing the video camera around in order to take footage of plasma and flames visible outside the windows of the orbiter (a normal occurrence). The recording, which on normal flights would have continued through landing, ends about four minutes before the shuttle began to disintegrate and 11 minutes prior to loss of signal between the orbiter and Mission Control.

Return to flight

After a two year postponement of the US Shuttle program, on July 26, 2005, Space Shuttle Discovery cleared the tower on the “Return to Flight” mission STS-114, marking the shuttle’s return to space. Overall the STS-114 flight was highly successful, but a similar piece of foam from a different portion of the tank was shed, although the debris did not strike the Orbiter. This time high resolution photos were ordered taken from space, and the crew carried materials on board should a mid flight repair be ordered.

Odd Facts

Worms on board Space Shuttle Columbia survived the crash. Sealed inside a heat resistant locker, the C. elegans stayed alive upon impact, because by the time that part of the shuttle fell to the ground, it had already decreased in speed, allowing the nematodes to touch down more gently. They were flown back to the space station via Space Shuttle Endeavor in 2011.

Debris Search Pilot Jules F. Mier Jr. and Debris Search Aviation Specialist Charles Krenek died in a helicopter crash that injured three others during the search for debris.